Vows and Commitments

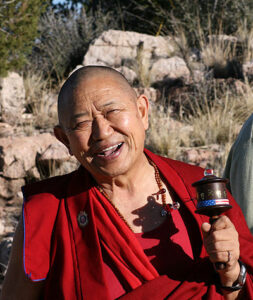

Garchen Rinpoche

To understand sacred commitments related to Vajrayana empowerments, it is necessary to place them in the general context of Buddhist vows.

Refuge vows

Those who follow Buddha’s teachings begin the path by first taking the refuge vows, placing themselves under the protection of the Three Jewels, the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha.

Lay people and monks

It is then possible, if the disciple has personal aspiration, to take the vows of a lay person (Sanskrit, upasaka; Tibetan, genien).

There are five vows:

- not killing,

- not stealing,

- not lying,

- avoid sexual misconduct, and

- not consuming alcohol.

They can be taken at once or partially, for a complete lifetime or a definite duration of months or years.

Taking these vows is not an obligation. In many Buddhist countries, men and women, without taking them formally, try to respect the ethical ideal that they represent by avoiding the ten negative acts and by practicing the ten positive acts.

Historically, it was often the case that kings governing these countries were eager to integrate the essentials of this ethic into their legislation.

On a more elaborate level, lay people will practice refraining from sexual misconduct by being chaste. The practitioner is then called brahmacharya (Tibetan, tsangcho genien).

Then come the monastic vows: minor ordination (Sanskrit, shramanera; Tibetan, getsul) and major ordination (Sanskrit, bhiksu; Tibetan, gelong).

Traditionally, one counts seven different ordinations that allow one to observe perfect ethic:

- upasaka men and

- women,

- shramanera men and

- women,

- bhiksu men and

- women,

- to which the women students (Tibetan, gelopma) are added, representing a type of vows reserved for women.

Temporary or definitive vows

In Tibet the monastic vows-shramaneras and bhiksus-were taken for life. It was not conceivable that the person who had taken monk’s robe could leave it in his lifetime. In Burma, Thailand, Sri Lanka, and in other Buddhist countries, the same vows can be taken for a lifetime, but also for limited periods of weeks or years. These two approaches are not contradictory, as both seem to have been envisaged by the Buddha himself.

In Thailand, the custom of temporary monastic vows has even been institutionalized. It is a duty for young men and women to devote at least few months of their existence to monastic life, by taking vows allowing them to live in a monastery. At the end of this period, those who wish can renew their vows and definitively adopt monastic life.

Otherwise, young people return to lay people’s life and establish a family. This monastic period is looked at as a proof of the quality of the individual. Boys or girls who would not

submit to it would have difficulty in getting married, because there would be a question as to whether they possess the moral qualities and necessary rigor to manage a family.

The different types of vows defined under the expression of individual liberation vows belong to the Hinayana.

In the Mahayana, there is another type of vows called bodhisattva vows, that are transmitted by various authentic lineages.

Monks and yogis

In andent India, two types of people, in a Buddhist context, have been looked upon as examples deserving respect and worthy of the material support of anyone. They were monks and nuns, whatever the degree of ordination; they were perceived as observing perfect ethics and having a lifestyle entirely in agreement with the Buddha’s teaching.

There were also those whose meditation practice had produced states of realization. It is the state of an arhat in the framework of the Small Vehicle, achieving the nonself of the individual. In the framework of the great vehicle, it is the bodhisattva who realizes the absence of own reality of self and phenomena, and also the Vajrayana practitioner who achieves mahamudra.

Reference to the ideal Buddhist was thus twofold:

- outer monastic commitments and

- inner realization.

Given that the first teachings of the Buddha focused on the Four Noble Truths and Hinayana in general, the first great historical disdples belong to this vehicle. Shariputra and Maudgalayana, two of the monks closest to the Buddha, the Sixteen Elders, or the group called the Five Hundred Arhats, are all looked upon as models of the small vehicle.

Later, there was a tendency to integrate the foundations of Hinayana and Mahayana in the same person, in other words, the monastic and bodhisattva vows. The most remarkable beings representing this were the Six Ornaments of This World and the Two Sublimes Ones.

Following this example, this approach spread throughout India. In Tibet, all three levels were simultaneously introduced. There are the ordination in accord with the ideal of individual liberation, the bodhisattva vows, and the Vajrayana approach.

Beginning with King Ralpachen, two groups, in spite of their differences, began to represent the Buddhist ideal. They are the group of the monks and the group of the lay yogis, characterized by their long hair and white clothes.

Importance of Hinayana vows

Those who take the major ordination must respect 253 rules related to the life of a bhiksu. Those who take the bodhisattva vows must practice the related precepts. As for the Vajrayana commitments, they are associated with and are given with empowerments.

Hinayana vows are, in a way, the basis on which the practice of the Buddha’s teachings develops. For this reason, they have a great importance and are sometimes seen as indispensable for approaching other levels. The bodhisattva vows are transmitted through two lineages: the lineage of vast activity and the lineage of deep wisdom. In the framework of the first lineage, the bodhisattva vows cannot be received unless monk or brahmacharya vows have been previously taken. In the context of the Vajrayana, the importance of the Hinayana vows is also emphasized. In the Kalachakra tantra, for example, it is declared that to receive Kalachakra empowerment, the best condition is to be a bhiksu, or at least a shramanera, this state being itself superior than the state of those who have no vow.

Sacred Vajrayana commitments

The Vajrayana, as Hinayana and Mahayana, implies vows, or sacred commitments (Sanskrit, samaya; Tibetan, damtsik) related to the empowerments.

An empowerment carries in itself a great force, a powerful blessing, and an important manifestation of compassion. The benefit of the empowerment obtained by the disciple largely depends, however, on the observance of sacred commitments accompanying it. It is said that if commitments are respected, the disciple will obtain liberation, if they are transgressed, the disciple will fall into inferior realms. To understand how crucial these commitments are in the Vajrayana, it is said that a follower of this path is like a snake trapped in a bamboo stalk. There are only two possibilities, to ascend or descend; exiting on the side is impossible. In the same way, the Vajrayana practitioner, whether respecting or transgressing the samayas from the empowerments he or she has received, can only ascend or descend without choice of a third path.

The three doors are the body, speech, and mind of ordinary beings. The three vajras are the Awakened body, speech, and mind.

From a certain point of view, the commitments of the Vajrayana may appear impossible to observe, because there are so many. The major monastic ordination already has a relatively important number of rules, 253 rules for the monks (bhiksu) and 440 for the nun (bhiksum). Some tantric texts claim that there are no less than 10,100,000 samayas related to the Vajrayana practice! However, when one understands the function of the Vajrayana and even more when one is truly committed to its practice, things appear easier. Indeed, it is said that the identification of our three doors to the three vajras of the deity is enough for the observance of the 10,100,000 samayas. This means that all commitments are maintained to the extent that one’s body is assimilated to the deity’s body, one’s speech to the mantra, and one’s mind to the meditative absorption (Sanskrit, samadhi).