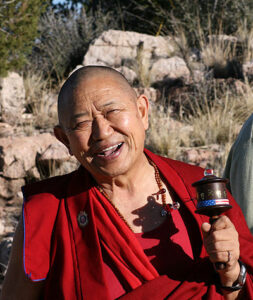

Teachings on Jangchok, the “Inscription for the Dead” – H.E. Garchen Rinpoche

Burning Away Afflictions

Translated by Ina Bieler, and transcribed by Ruyu, Rebecca, and Greg in 2018; edited by Dan Clarke in 2019.

My Dharma friends, this is an introduction to the “Jangchok” practice, also known as the “Inscription for the Dead.” Although here we are speaking in terms of the religious tradition, it is the same in the mundane tradition, as they share an intention regarding the death of loved ones. In both traditions, when a parent or relative passes from this life, we remember them by name and we remember the love we have for them. We place their name and picture on a shrine, and in that way we honor them and send them love. Also, we often buy a grave and set aside a piece of land and so on, which is very expensive. In general, all of that is good because it is an act of generosity.

Ultimately, though, this cannot protect them from suffering. Even if someone possesses perfect wealth, they still cannot escape the suffering of samsara. They still experience mental agony, or they get sick, or they are harmed by spirits, enemies, or obstructers. In the end, no matter how many jewels someone may possess, no matter how wealthy someone may be, these things cannot clear away the suffering in their mind. And those who are poor suffer from a lack of possessions, so they are not beyond suffering either. These are not the ways to freedom from suffering. However, a method does exist that can help beings on the level of the mind—where it can really benefit them—and that is to practice Dharma, such as this “Inscription for the Dead,” which is a ritual for purifying the obscurations of the mind.

There are different types of protection available that can shield us from suffering in the short term, and ultimately help us to reach liberation. The worldly gods, for example, can protect us temporarily in this life, and they can help us attain perfect enjoyments, wealth, and riches. And for most people, gathering wealth for only this life is sufficient; that is all they really care about. Most people don’t think about karma and future lives at all. However, if one engages in practice intending to only achieve something for oneself in this life, this is called a selfish motivation. The afflictive emotions arise from this mind of self-clinging, and they lead to rebirth in any of the six realms of samsara, depending on which afflictive emotion is most prevalent.

It is these beings in these six realms of samsara for whom we are performing this “Inscription for the Dead” purification ritual. We will start in the middle of the text and go to the end, and then go back toward the beginning. We begin on page thirty with the section on the dead, the objects of this purification.

The text here begins with Om Ah Hung and continues by speaking about the six classes and the five types of beings—the objects of this practice. At the very beginning of his teachings, the Buddha said: “All beings are actually buddhas. Beings are only obscured by adventitious stains.” Due to these stains, they perceive only ordinary body, speech, and mind, which by nature are actually awakened body, speech, and mind. In reality, the ordinary appearances of body, speech, and mind lack any inherent or real existence, though they appear to sentient beings in such a way that they believe in their real existence. This belief in the real existence of outer appearances and their conceptual labels is what creates the six realms of samsara.

The natural state of the mind of all beings is buddha-nature. The awakened body, speech, and mind of the buddhas, and the ordinary body, speech, and mind of the beings in the six realms of samsara have a single basis. The Samantabhadra Prayer says: “There is a single ground, yet two paths.” One is the path of the afflictions, which arises from the self-cherishing mind that clings to the existence of a self, and the reality of outer appearances and their conceptual labels. These beliefs are what engender afflictive emotions, which lead us to engage in negative actions. It is through our negative actions that we accumulate karma, which causes us to be reborn in the six realms of samsara.

For example, it is like a big tree with roots growing deep into the ground. The deepest parts of the roots represent the three lower realms of samsara, while the trunk and upper parts of the tree represent the three temporary higher realms, all the way up to the ultimate state of enlightenment, which is the buddhas’ three kayas—the dharmakaya, sambhogakaya, and nirmanakaya. The human world is actually said to be a nirmanakaya pure land, while the dharmakaya and the sambhogakaya are the pure aspects of a Buddha. The nirmanakaya has both pure and impure aspects, such as in the human realm where buddhas and sentient beings coexist, as they are both by nature nirmanakayas.

How do these realms of samsara come about? The six realms of samsara are the creation of the six kinds of afflictive emotions. Everyone actually possesses all six of them, but to different degrees, and whichever affliction is most prevalent determines our future birth. For example, if greed and stinginess are most prevalent, one will experience the poverty, hunger, and thirst of the hungry spirits. Or if hatred and anger prevail, one will experience the suffering of burning in hell. It is taught that one can take birth in samsara in four different ways: through a womb, an egg, miraculously, or through heat and moisture. Within these four types of birth there are endless possibilities of forms one can assume. These suffering beings in the six realms of samsara are the objects of our compassion.

Beings suffer in samsara because they have not realized the nature of their mind. By not seeing their true nature, their mind is confused. Though self and others are in reality inseparable, beings become confused by perceiving themselves to be separate individuals, which causes them to grasp at the true existence of whatever appears. Through this grasping they develop feelings of attachment and aversion toward appearances, which leads them to further confusion and further circling in samsara.

What kinds of suffering do these beings experience? As an example, a being could be born as one of two kinds of hungry spirits: one who suffers from outer obscurations, or one who suffers from inner obscurations. Both experience the suffering of poverty, hunger, and thirst. It says here in the text that these types of beings are all the guests of my compassion, the two classes of impoverished hungry spirits, and all those who have left behind their physical supports… you who have not yet found your future bodies. These particular beings in the six realms, as well as all others who have passed away—those who have cast aside their old bodies and have not yet found their future bodies—are the guests, the objects of our compassion.

We said that the human world is like a pure land, a nirmanakaya realm. Nirmana means “emanation,” and kaya means “form” or “dimension,” so a nirmanakaya is an “emanation form.” In the nirmanakaya dimension there is both happiness and suffering, pure and impure. For example, if in a past life one created some virtue, as a result one can experience some happiness as a human. However, since one has also done things in the past with an afflicted, selfish mind, one also experiences suffering in the human world—though unlike the suffering of the three lower realms. Sentient beings in the lower realms primarily experience what is called “suffering upon suffering.” In such a state of torment, the mind is very solid and coarse, like a block of ice, and the afflictive emotions run entirely unrestrained. They remain in this ice-like, crudely compressed existence until the karma that caused their birth in that realm becomes exhausted. In contrast, the human realm is like water and ice existing together, as there is both happiness and suffering. There are afflictive emotions, but there is also love. This is the realm of the nirmanakaya.

What happens in the bardo after someone has died? If there was virtue in the mind at the moment of death—for example, the boundless mind of love—the consciousness will naturally move to a more fortunate world. It will take birth in the higher realms, the pure lands, and ultimately attain buddhahood. It will not remain in the bardo for long. If, on the other hand, one dies in a state of self-clinging and affliction—for example, as someone who has never believed in karma, cause, and effect—or if one has committed very heavy negative deeds, then one will instantly go down into the lower states of existence after death.

This happens because the moment you die, you are taken by the winds of your afflictions; you follow your karmic winds. How does this happen? For example, imagine you have a companion whom you love very much, from the bottom of your heart—but one day you get angry at them. If you do not recognize your anger and instead allow it to control you, the winds of the afflictions will carry you away. Driven by anger, you do or say things you normally wouldn’t. You might leave your companion, or even hit or kill someone. Without awareness, you become controlled by these karmic winds, which are nothing else but your own afflictive emotions. After death, in the same way, if the mind is taken by the karmic winds of anger and hatred, they will take you to hellish states. Or if the mind is taken by the karmic winds of greed and stinginess, these winds will take you to the world of the hungry spirits.

In reality, the workings of karma are much more intricate; it is not all so straightforward. Because each kind of afflictive emotion can be combined with another, there are myriad types of thoughts and emotions. For example, there are different forms of attachment: angry attachment, jealous attachment, greedy attachment, and so forth. All of these emotions are driven by ignorance, and when the mind is ignorant, whatever we do will be mistaken. In any case, if afflictive emotions become completely unrestrained and uncontrolled, they will lead to “suffering upon suffering” in the three lower realms. The suffering of the three higher realms is different in that we primarily experience the “suffering of change.” As was mentioned, human existence has aspects of both, like water and ice co-existing. This is the first point we should understand.

If one has come to understand or at least has heard of karma during one’s lifetime, then even if one has not been able to do much practice—and even though one’s mind may still be afflicted— the consciousness can remember and understand everything after death. For example, if strong anger arises in such a mind, one may remember the importance of practicing love and patience. It is by remembering patience, love, and compassion that you can protect yourself in this and future lives. Even though you may get angry when you feel that someone has wronged you, if you understand that expressing this anger will ruin you and the other person, you can still control it by practicing patience and reminding yourself of karma. People often think that patience is a Buddhist practice and that what others in the world are practicing is not Buddhism. However, someone else, a “non-Buddhist,” might have already developed a strong sense of love and compassion, and they might be able to practice patience quite naturally. Actually, there are lots of people who are able to practice patience. Whichever path one enters depends upon various outer circumstances, but mainly what actually makes one a “Buddhist” is the power of one’s love, patience, and compassion.

Regarding the length of time one spends in the bardo, there are generally two different situations. In the first, the consciousness spends about forty-nine days in the bardo, though this is also not so straightforward, and the amount of time is actually uncertain. The second situation occurs when someone dies a sudden or untimely death before their natural life span has passed. That being’s consciousness stays in the bardo until what would have been their natural life span has passed, however long that may be. After that time, if one has the support of virtue in one’s mind, one can go on to a pure land. If not, then whatever karma has been accumulated will cause one to wander anywhere in the six realms of samsara.

There are also some bardo beings who may temporarily appear as spirits, local gods, or territorial spirits. These beings are also referred to as sky-faring hungry spirits. Their life span in the bardo can be very long, even thousands of years. They suffer from hunger and thirst, and so forth. For this reason, it is very beneficial to make offerings to these beings, for instance, by performing smoke offerings. When the Buddha was alive, some local and territorial spirits took lay person’s vows in the presence of the Buddha, and also later in the presence of Guru Rinpoche, and were thus bound under oath. They are still alive and they will remain in that state even until the next Buddha comes.

The bardo beings with the shortest life span are those who have committed suicide. Though people commit suicide because they want to run away from suffering, after killing themselves, they will go on to experience the circumstances of their death over and over again in the bardo. Every seven days, they will experience the same suffering of killing themselves, and this happens over and over… again developing hatred, and again killing themselves, for it is said that each action bears a karmic debt multiplied by five hundred. After they have experienced this repeated re-living of the conditions of their death, the results of full karmic maturation finally come into effect, and they take rebirth in hell, where they will have to experience the consequences of their actions for a very long time.

Then there are those who have committed heavy negative deeds. Again, whatever condition their death occurred under will be experienced again and again, every week, until what would have been their natural life span has passed. There are many practices, such as this “Inscription for the Dead,” that we can do to help these beings by purifying their obscurations. For example, there are the “forceful deliverance” practices of Yamantaka and Vajrakilaya where, even though a being’s life span might not yet be exhausted, it is cut short by forceful means. Through this forceful deliverance, these beings are raised up to take birth in the higher realms or pure lands. Otherwise they would have to remain in a miserable state for a very long time. So, while there are many explanations in terms of life span, in brief we can say that the life span in the bardo is uncertain.

Page thirty refers to these beings as lost on the dreadful paths of the bardo of becoming, without refuge or shelter, protection, or helping friends. While we are alive, we may have companions who protect us. For example, in the beginning, our parents and our worldly teachers protect us by teaching us how to live in the world. Later in our lives, our spiritual teachers teach us about karma and about how to cultivate love and compassion, bodhicitta, and so forth. After we die, in the bardo, whatever is present in the mind will be projected as an appearance. If the love we have learned from our teachers is present, these projections will appear in a friendly way, for love naturally projects pleasant joyful visions. If there are anger and jealousy in the mind, these will naturally lead to projections of enemies and threats. Everything in the bardo is the projection of one’s own mind.

In this practice, here we are speaking about someone who has not developed love and compassion. Without love, one is without refuge or shelter; one is in a dark place with no protection, no companions—all alone. Some people, while still alive, are very selfish, and they can only think about what’s good for themselves, what they want. They are very afflicted. And the more afflicted the mind, the more one sees everyone else as an enemy, a threat, an irritant— as someone one just doesn’t like being around. That even goes for one’s own parents, relatives, and friends. For example, nowadays we hear about children being shot in schools.

Even now, everything you perceive is a projection of your own mind. Mostly our self-clinging is too overbearing; in fact, it is the most powerful force governing our lives. Even before the bardo, one perceives everything as a threat, as an enemy, as reproachable. Actually, in a way, we have already crossed the boundary between this life and the next.

In the bardo, appearances will manifest in a similar way. Now while you are still alive, experiences are less intense than they will be in the bardo. Now you might still be able to relax your mind a little and practice a bit of patience. But still, if you do not know how to seek refuge in the Three Jewels properly, there will be no protection later in the bardo. So, regarding the bardo beings, the text says: You have no support of past collections, and little virtue to call upon. This refers to a being who did not practice much Dharma and virtue during their life. They have not practiced the deity and they have not meditated or recited mantra. If you have not trained in any of these, you have little virtue to call upon.

This line also points to the support you can give to others. When we practice on behalf of those who have passed away, that becomes a virtue, a support for them to call upon. It is a merit we create for them, and it can guide the deceased along the path to happiness. It can help them become liberated. But if you have none of this to call upon in the bardo, the text says: In the aggregate of four names, feeling is the nature of suffering. This is because when you die, your physical form is cast aside, and the aggregate of the body is left behind. But even though you no longer have a physical form in the bardo, you still have the other four aggregates—you still have feelings, perceptions, karmic formations, and consciousness, just like now. And like now, you experience feelings of happiness, suffering, and so forth.

Nowadays most people in this world only think about themselves, and this fixation is very powerful. No matter how much wealth some people possess, they are never truly content, never really satisfied. Naturally, they mostly suffer; they are miserable and unhappy. They think that no one likes them. They are on a lonely path, just like in the bardo—except that in the bardo this lonely path will torment them even more than in this life. They will experience the same feelings they had during their lifetime—the suffering of hunger and thirst, heat and cold, just like now— except that in the bardo these feelings will be intensified.

The reason for this lonely path in the bardo is due to the clinging to an “I,” which isolates you and creates the illusion of being a separate, lone individual. The ultimate nature of this isolation is suffering and fear; there are always feelings of great fear toward the terrifying perceptions and visions present in the bardo. Tormented by these perceptions, the perceived lone individual wanders in a bewildered state, constantly thinking that something terrible is about to happen, that someone or something is going to hurt them. It happens now too—even when you just see a mosquito, you think, “It’s going to bite me.”

So, beings in the bardo experience intense fear. This is an important point because if we understand what their fear is, we can cultivate compassion for them. If we do not understand the basis of their fear, this will be difficult. In order to understand their fear, we must first of all bring to mind the fear and suffering we ourselves have experienced. For example, I myself experienced it during the Cultural Revolution. Many people in independent, free countries like the USA cannot really understand that kind of fear. Imagine an invasion where everything is destroyed and there are enemies all around who want to kill you. You need to run away and hide, but there is nowhere to go, nowhere to hide. There is no protection anywhere. This generates an overwhelming feeling of fear.

Another way to understand their fear is to think of someone whom you love very much, like your mother or a relative or a very dear friend, and imagine that this person is roaming about all alone in the wastelands. The weather is frigid, and they are freezing and naked. They have no food and they are afraid. By thinking in this way, love and an unbearable feeling of compassion will naturally arise. How would you feel if you had to wander around in such a terrifying place with ferocious wild animals, where it is snowing, it is freezing cold, you are naked, you are on your own, and you have no support to call upon? Most bardo beings experience this uninterruptedly. Only if you really understand this will you be able to give rise to compassion for these beings. Take this as a basis and apply it to these beings.

Regarding them, it says: Like a feather blown around by the wind, you have no control over where to go. We dedicate the offerings we have gathered to these specific beings in the bardo, as well as all other beings in the bardo—those whose minds are “like a feather blown around by the wind.” You might think that this is only how it is in the bardo, but actually that’s not true: it is also like that here, right now. The Buddha said: “Meditate and look at your own mind. Then you will see.”

When looking at your mind, you will see that your habitual ways of thinking constantly arise, like dust motes in sunlight. This habitual thinking happens naturally, all the time; it is almost as though you have no control over your mind at all. We usually lack any awareness of these thoughts, and because of this, some people feel that their state of mind is actually getting worse when they start meditating and looking at their own mind. But actually, that is not the case. These thoughts still arose when you were not meditating—you were just not aware of them. In fact, without the self-control of mindfulness, myriad habitual thoughts arise constantly, and habitually you follow them. For example, when you get angry, you are instantly controlled by that anger. You act out on it and end up arguing with someone. Whichever of the three afflictions arises, you are automatically controlled by it. Right now, we can understand this when we meditate, when we look at the mind. So, though it seems like thoughts are increasing, we are really just becoming aware of our thoughts.

Unlike in the bardo, we now have a precious human body. We care so much about this body that it basically exists as our sole focus: we need a nice place to live, etc., and we become like ants running around busily taking care of it day and night. But now, in this body, we have an opportunity to actually look at our own mind. In this precious human body, we have a chance to realize the nature of mind through meditation practice. When you meditate and look at your mind, you can clearly see the habitual thoughts arising. If you understand this, you will want to practice taming your mind by cutting through these habitual patterns, because if you don’t, you will be in trouble later on.

When we practice this ritual for purification, or when we perform burnt offerings for the deceased, what really benefits them is the merit we accumulate. They suffer because of their afflictions, their greed for example, and the generosity of this ritual purifies their obscurations of greed and stinginess. So when we perform this purification ritual, what they really receive—the actual benefit—is our love. Though they receive your offerings by virtue of the three powers— the power of your love, the power of the Three Jewels’ compassion, and the power of dharmadhatu—what they really receive is love.

Considering this, on page thirty-two we pray: May you be at ease, having met with perfect dwelling places, companions, enjoyments, food, and drink. This itself is a dedication of love, and because these beings can feel your love, the moment you think of them in this way, their self-clinging diminishes. For example, if a friend whom you love very much is sick and you go to visit them, the moment they see you, they immediately feel better, they feel happy. A special feeling arises because they can feel your love. So when you practice the “Inscription for the Dead,” you mainly need to give your love to others, and it can reach them by virtue of the three powers.

In the next line we pray: May you recognize the bardo as such and seal confused appearances. Remembering the guru, the Three Jewels, and so forth. “Confused appearances” refers to the perception of self and others as being separate. “Sealing confused appearances” means that by giving rise to love and compassion, the concept of a separate self will collapse, and along with it all confusion and all confused habitual imprints. This happens because outer appearances are nothing other than the projections of our own mind. For example, when you are angry, you naturally perceive all external appearances as enemies, as threats. When there is no more anger and instead you have love, the external appearances will transform, and everyone on the outer level will naturally appear friendly, as good. For example, if you let go of confused perceptions, instantly everyone here in this room will appear as your friend. The remaining lines on this page are very clear: Remembering the guru, the Three Jewels, the yidam, and the view, may the obscurations of all misdeeds be instantly purified. Thus, may you attain mastery of awareness.

This dedication of love—may you be at ease—is very important, and it is also a concept that we must relate to our own experience of ease. What is the feeling of “being at ease?” Earlier, we brought to mind our frightening experiences in order to understand the fear that beings experience in the bardo. When we thought of the dreadful paths these beings must traverse, what came to mind is their suffering, and in particular their suffering of intense fear. Through this, an experience fear arose in our mind.

Now that we are dedicating our roots of virtue to these beings in the bardo, we wish for their minds to be at ease, which is a feeling we must also relate to. As an example, when you are with your loving friend at a nice restaurant with lots of delicious food, you feel at home, you feel at ease. When you are with a dear friend that you love, without even saying a word, you naturally feel at ease, like you are with family. Your mind is relaxed and at peace, and you experience well-being and happiness. Through bringing to mind a memory of this from our own personal experience, we can understand what we wish for these bardo beings. So we develop the wish that they also receive this feeling of peace. You may wonder whether they can truly receive your dedication, but if your love for them is pure, you can be confident that they are receiving your dedication, and that you are actually benefiting them.

In the second line on page thirty-two, we pray: May you behold Noble Avalokiteshvara and the Bodhisattva Eliminator of Obscurations. In the bardo, as the consciousness roams throughout the entire world, all of its positive and negative karmic imprints can arise. Therefore, if you have received just a single empowerment of Avalokiteshvara, and during the empowerment you received a picture of the deity, you then carry within you the awareness of having received that empowerment, and you can recognize the deity through having seen the picture. Further, it is taught that by having received an empowerment—even if one does not practice that deity during one’s life—simply by having faith and great love for the deity, that deity can naturally appear in the bardo in an instant. By merely hearing or remembering the name of that deity, the form of the deity can appear, and you can behold the deity directly and clearly understand the meaning of any transmission you received during your life. This is why it is so important to receive a picture of the deity during an empowerment. It is through seeing the image that we recognize the deity, which will be very beneficial in the bardo.

Remembering the deity relates to the last line of that page, where it mentions “remembering the view.” The view consists of the two-fold bodhicitta—in essence, love and wisdom—whereby the obscurations of all misdeeds are purified at once. The obscurations of all misdeeds are nothing else but self-clinging: all our negative karma accumulated since beginning-less time in samsara—all obscurations and misdeeds, all negativities—arise from self-clinging. And when self-clinging is destroyed, all karmic imprints naturally disappear. For example, when you think of Avalokiteshvara, at that moment there is no concept of a self, which is why it is so important to meditate on the deity. Even if you only practice the deity for five minutes, to that extent self-clinging is diminished. Also, if you give rise to immeasurable love for just a moment, in that moment there is no self-clinging. Then if self-clinging arises once again, the afflictive emotions will also arise. It’s like the weather—when it gets cold at night, the water freezes into ice, and when the sun comes back out the next day, it melts a little bit again.

Therefore, we say: Thus may you attain mastery of awareness. When one has attained mastery of awareness, the mind cannot ever again freeze into a block of ice. Even in the bardo one will remain within the state of bodhicitta. Right now, while we are still alive, because we don’t experience much hardship, we often develop pride. We approach practice quite casually. We think that it is okay to receive an empowerment, but that it is also okay not to; or we think that we can do some recitations, and if we don’t feel like it, that’s also fine. This is because we are too distracted by this world, which is quite similar to the distractions of the god realm.

Later in the bardo it will be very different. Terrifying appearances will manifest, and there will be nowhere to hide, no refuge. For example, in communist prison labor camp, people were so hungry they would even eat their own or others’ excrement. Here right now we don’t see this kind of suffering, but at that time there was so much suffering. In the bardo it is like that—beings are desperate like prisoners, and they reach out for any help. So, if the bardo consciousness feels that something could be of help, they will instantly develop faith in it. There is no pride at that time; there is only torment by terror and fear. One wants to find any way out. If they develop faith while in that state, their consciousness can become liberated, so the next line requests for them to pass with sudden force to special pure lands, such as Dewachen or Lotus Light!

How does the “Inscription for the Dead” work? As an outer example, if you have a dear friend who is far away and having difficulties, you can help them out by wiring money or mailing things to them. This is very similar to the “Jangchok” practice. To be permitted to engage in this practice on behalf of someone else, there are two criteria you must possess. The first and most important is bodhicitta: you must have immeasurable love for all beings, as this is first and foremost an activity of love. The second criterion is that you must have taken the refuge vows, and ideally the bodhisattva vows. When these criteria are complete, the way of benefiting these beings in the bardo is just like sending something to a friend in the mail.

If you want to send something in the mail, you can’t send it all by yourself. You also have to rely on the other citizens of the country to deliver it. Similarly, when you have taken the refuge vows, you become like a citizen of the country of the Three Jewels. As a citizen, you have to follow the laws of the country, and here, these laws refer to any of the vows you have taken, such as the four root vows, or even just one single vow.

As a citizen of the Three Jewels’ country, you must observe these vows. In order to benefit from the country’s power and the services available, you have to participate as a good citizen. In brief, the laws you really need to follow are the refuge vows and boundless love. You need to really understand the qualities of love and, ideally, you would also understand that self and others are in reality not separate—though this is a bit difficult in the beginning. We can understand this eventually, but for now this is still an intellectual understanding. What is more important for us right now is to possess boundless love. If you have that, you are able to actually benefit sentient beings, and therefore you are certainly permitted to engage in this practice.

Going back to page two in our text: the accomplishment of the “Jangchok” practice is due to the three powers. The first of these is the power of your own pure intention, which is conventional bodhicitta—immeasurable love, essentially. Then if you have realized the ultimate truth—that self and others are inseparable—you can truly benefit others with your intention. At that point you become very powerful, like the king of the Three Jewels’ country. This first power is the most important one.

Second, there is the power of all the buddhas’ great compassion. The buddhas have found only one precious jewel: precious bodhicitta. This love is what the buddhas of the three times give to sentient beings; it is the only intention of all the buddhas. It is their enlightened mind, their realization. Having taken the refuge vows, you received the love of all the buddhas of the three times. This love is what generates the power of merit.

Even before they attained enlightenment, it was their intention of love that motivated them on the path, became the path, and caused them to attain awakening. In the beginning, they all developed bodhicitta—the mind of awakening—and without it, they would never have attained enlightenment. So now, when you give rise to love and merge it with the enlightened mind of all the buddhas of the three times, you are merging your merit with the vast merit of all the buddhas. This is like everyone in the world combining their money into a single bank account. How powerful would that be? Similarly, you combine your merit and compassion with the merit and compassion of all the buddhas.

The third power that brings about the accomplishment of the practice is the power of the dharmadhatu, the single basis. It is by virtue of these three powers that we can accomplish our aspirations and activities. So after taking the refuge vows, you should give rise to a clear mind of immeasurable love. This state of mind is the foundation of Dharma practice.

On page two, we consecrate the vase. The foundation of Vajrayana practice, the actual view of Vajrayana, is pure view. The mind is temporarily in an impure state, obscured by the five afflictive emotions, and when these five afflictions mature and transform, they mature into the five kinds of primordial wisdom. All forms are actually the projections of these five wisdoms manifesting as the five elements. In reality, everything is interconnected: your own body, the bodies of others, and the outer universe all consist of the same five elements.

Here we are consecrating the vase, as well as the nectar-water inside the vase, which has the nature of the five primordial wisdoms. In particular, it has the nature of mirror-like wisdom, which is the true nature of water. In its impure state, the element of water is related to the affliction of anger or aggression, but when anger becomes purified, it has the nature of mirror-like wisdom.

These five wisdoms are not separate from each other. For example, they are like the five-colored lights reflecting from the facets of a crystal. A rainbow is also like the natural manifestation of the five wisdoms. There are two important Dzogchen terms: original purity and spontaneous presence. Original purity refers to the nature of the basis—symbolized by the crystal—which is that everything is inherently empty. Spontaneous presence, which is like the light shining through the crystal, refers to the spontaneous appearance or natural arising of everything—for example, rainbows, rain, clouds, and the sky.

The outer form of the vase—the vessel itself—represents the boundless palace of the deity. The nectar-water contained within the vase is by nature the deity. It can be any yidam deity you are personally connected with, to whom you are devoted. Today we will take Tara as an example since it is one of our main practices. Tara is very powerful in clearing away various kinds of fears, such as the eight or sixteen kinds of fear. Her dharmakaya nature is the great dharmakaya mother, her sambhogakaya nature is Vajravarahi, and her nirmanakaya nature is Tara appearing in this world. She appears in this world in many different forms, such as Machik Labdrön, Yeshe Tsogyal, Mandarava, and many others. Atisha composed a supplication to Tara that is very powerful for clearing away fear and obstacles, for closing the doors to the three lower realms, and for guiding beings to rebirth in the higher realms. This supplication can truly protect you from all temporary and ultimate suffering. It is through this consecration of the nectar-water that the obscurations of sentient beings are purified. In fact, because all beings possess buddha-nature, the sentient beings to be purified are actually already pure by nature; they are only temporarily obscured by self-clinging, which causes their mind to be like a block of ice. This is an outer example.

That which purifies self-clinging is bodhicitta, which is like the warmth of the sun. When this warmth melts the block of ice, the water merges with the ocean. The buddhas also had to melt their blocks of ice, and when they did, they attained the state of enlightenment. This is my personal understanding of it. This example might be suitable for people like me with not much learning.

On the bottom of page three, the deities melt into the wisdom nectar and merge inseparably with the vase water. The nature of all deities is primordial wisdom, which is represented here by the visualization. What is this primordial wisdom? When we have not realized the nature of mind, we call it dualistic consciousness. Dualistic consciousness thinks that self and others exist separately. But when you look at the essence of this consciousness, you see that no separation exists between yourself, the deity, sentient beings, the buddhas, and so on. It is like the ocean that knows it is not separate from the blocks of ice floating on its surface. Only the blocks of ice believe they are separate from the ocean water, so temporarily they suffer. This is why again and again we say that all beings are actually buddhas, and that they are only temporarily obscured by the thoughts in their minds. In brief, all of this comes down to self-clinging, which is eliminated by love and compassion. When the ice block of self-clinging has merged non-dually with the ocean, this state of mind is referred to as “space-like, non-dual primordial wisdom.” There is space, but there is no duality, no division within space. The dharmakaya is like space: it is primordial wisdom, which is the nature of all the deities.

On the bottom of page three, there is the supplication to the guru: I pray to you, precious guru, kind Lord of Dharma. I call you with longing. What makes the guru a precious guru is not his body. More precious than the guru’s body is the guru’s speech, his words. It is through the guru’s words—the teachings—that we can understand the workings of karma: what we should and what we should not do. What is the benefit of this? If you really understand karma, you have an answer as to why you are suffering. Suffering is a purification of misdeeds, of negative karma, and knowing this helps you tolerate and accept your own suffering. The root cause of this suffering lies in self-clinging, and the antidote to it is love and compassion. If you know this, you will know to sustain love and compassion. Understanding the workings of karma and what to do and what not to do, you learn how to take suffering as the path and how to practice with it. And you know that ultimately you can attain the state of enlightenment. So this knowledge was given to you through the words of the guru. He has given you a method to create happiness, temporarily and ultimately. This is how the refuge vows benefit you.

What is most important is the guru’s mind, and the guru’s mind is bodhicitta, immeasurable love. Through the guru’s kindness you can understand the quality of immeasurable love, as well as how to cause it to arise in your own mind-stream. Reflecting upon the guru’s kindness in this way, you will develop a sense of gratitude toward the guru, and therefore you should practice his instructions and give rise to bodhicitta.

The text says: Unfortunate ones have no hope but you, and here “you” again refers to bodhicitta. The buddhas of three times had no other hope than bodhicitta, which is why they called it “precious bodhicitta.” It is the heart of all the buddhas of the three times, and it is the actual mind of the guru. The bodhicitta in your own mind is your inner guru, and this is the actual guru to rely upon. Actually, it is of not much benefit to only care about the guru’s body, which can have both faults and qualities. It is more important to care about the guru’s words.

In order to summon the beings we are helping, we tell them: From the state of emptiness appears your initial adorned with a bindu. Limitless consciousnesses can be summoned and contained within the bindu adorning the initial, and here we call them to us by name. Though at this time they are circling around in the bardo, once they take birth within the six realms of samsara, they will have no more awareness of us calling to them. However, as long as they are in the bardo, their awareness is highly sensitive and their feelings are very intense. So we imagine that they are coming here to this place and gathering within the bindu above the initial. What appears here is their consciousness, and since they have no physical form, millions of consciousnesses can fit. There are also various ritual materials used here, such as the mirror and so forth, but these are secondary: most important is for us to think that the consciousnesses are all summoned here, and that millions can fit inside. It is essential to really feel that they are actually here. The lines in the text that follow speak about protecting them from suffering, as once they are summoned, they have to be protected.

On page seven we tell them: Resist the tempting calls of evil forces that will lead you astray. The bardo consciousnesses might hear voices calling to them, luring them. Since they wish to escape their state of fear and panic, they might be tempted to follow these voices. But the voices can lead them astray, so here we are instructing them to not listen to the voices, but rather to think of the Three Jewels or the yidam deity. We are helping them to direct their mind single-pointedly to the yidam or the guru. Otherwise, if they follow their habitual tendencies of wanting to escape, if they follow the karmic winds of their afflictions, they will continue to wander in samsara. In actuality there is no being calling to them—it is all in their own mind. Therefore, they should not listen to these voices. Instead they should instantly direct their mind to the yidam, the Three Jewels, or the guru.

On page eight we recite the summoning of the bardo consciousnesses three times. Here you are inviting their consciousness to come and remain here at this pleasant place, this boundless palace, which is just like a fancy hotel. Or you can think of it as a pure land, such as Dewachen. Think that now you are inviting the thousands of consciousnesses who have passed away, these very dear friends whom you love very much, to come here and stay in this nice hotel. Imagine that this puts their minds at rest and at ease, and that they are very happy and at peace here in this place. Then the consciousness dissolves into the support with JAH HUM BAM HO. These four syllables represent the four immeasurables—love, compassion, joy, and equanimity.

On page nine we see that a great mix of beings has gathered together here. You might think that among the bardo consciousnesses we’ve summoned, there could be some obstructers included, such as karmic creditors, who could cause trouble. Due to a dualistic perception of self and others, you might believe that these harm-doers could come in along with our friends, resulting in all kinds of bad things happening. In order to prevent this type of harm, after the consciousnesses have been summoned, we consecrate the hindrance torma with RAM YAM KHAM and OM AH HUM. With RAM YAM KHAM we cleanse and clear away all belief in a concrete reality, including all conceptual labels. With OM AH HUM the torma transforms into an ocean of primordial wisdom nectar. The text instructs them: All you dualistic and confused appearances—you spirits, obstructers and elementals—take this torma and go to your abodes. Think that by visualizing in this way and offering a torma, we repay all karmic debts to these karmic creditors, and that all karmic creditors, harm-doers, and obstructors are thereby cleared away.

We normally are attached to our friends and dear ones, while we have an aversion toward obstructers and so-called enemies. Though in actuality this is only how it appears to us, by offering a torma as a gift, all these fixations and karmic debts are purified. Because of this, think that now the remaining consciousnesses come to rest within a state of immeasurable love, a state in which there are no objects of aversion and no enemies. Also, if you yourself give rise to a mind of immeasurable love, it will help the consciousnesses to develop such a mind as well. This is because the basis of our mind is one. Therefore, as the one performing this ritual, if you give rise to immeasurable love, they can also give rise to immeasurable love. Here you should meditate on the inseparable nature of self and others.

On page ten, the six seeds of the six realms of samsara are burned away. The afflictive emotions of all beings, whether they are alive or have passed away, are exactly the same. Though beings appear in so many different ways, our afflictions are all the same. So here we burn these causes of the six realms of samsara in the form of their six seed syllables written on paper. Here we are not only purifying our own obscurations, but through the recognition that one’s own afflictions and the afflictions of all sentient beings are exactly the same, we are also purifying the obscurations of all sentient beings in samsara. Recall this while reciting the mantra, and think that you are burning away all obscurations that cause birth in the six realms of samsara.

Be sure to visualize the six syllables clearly. These syllables actually have the nature of the five primordial wisdoms. Our mind has the five kinds of afflictive emotions, and our precious human bodies consist of the five elements. On the secret, hidden level, when these afflictions mature and transform, they mature into the five primordial wisdoms. In this way, our ten fingers serve to represent the five Buddha families in union with their consorts. The five male buddhas, in their impure, immature state, manifest as the five afflictions, and they mature into the five primordial wisdoms. The five female buddhas, in their impure, immature state, are the five ordinary elements, and these mature into the five dakinis. The joining of the five fingers of both hands is like the union of the earth and sky, or the union of Samantabhadra yab and yum. Uniting the ten fingers here represents the union of the male and female buddhas of the five families, and within this, the entire universe and all beings are complete, as everything essentially has the nature of the five buddhas in union with their consorts. This union represents greatly blissful primordial wisdom, the blissful mind that burns away the seeds of all suffering. So here think that the six syllables that are the cause of the six realms of samsara are being burned away by this awareness.

Through this union of the deities, the afflictive emotions are transformed into primordial wisdom, which is something one can only experience personally. How are the afflictions transformed into primordial wisdom? How does one gain a direct experience of this? To give an example, for a practitioner who practices on an on-going basis, when anger arises, there is also an awareness of it arising. This awareness instantly recognizes the anger the moment it arises, which is how you can turn afflictive emotions into the path. If you continue to sustain awareness, the emotion will disappear. Once the anger has completely dissolved, the mind is crystal-clear, and you might even start laughing. This is the clear empty nature of the mind, and there is no trace of anger left behind. That is the first experience to gain. Then you habituate to this experience of resting in the natural state of mind, free from all thoughts and concepts. This state is by nature empty like space, and naturally clear. It is clear empty awareness. This clear empty awareness burns away all thoughts in the mind.

So, through the union of the male and female yab and yum, an experience of very sharp radiant awareness that is blissful and empty arises. There is no thought, no concept whatsoever. This so-called “view” burns away all afflictions, and not even the trace of a feeling is left behind. This is how we burn away the five or six afflictions. In the Samantabhadra Prayer, it says: “Let awareness rest in its natural state so that awareness can hold its own.” In just this way, all afflictive emotions are eliminated. As we burn the fire, with each recitation we visualize in this way.

Turning to pages fourteen and fifteen, we offer ablution, which is the offering of a sacred bath to a representation of the Buddha’s body, speech, and mind. We then offer robes to that representation and pour the water back into the vase, where it transforms into a nectar of the deity’s bodhicitta. On page fifteen, the second line says that its water cleanses the stains of the six afflictions. This is the water of conventional bodhicitta, and as nectar it cleanses the self-clinging in the minds of all sentient beings. When directed toward sentient beings, whatever you do with your body, speech, and mind with a motivation of bodhicitta naturally becomes a practice of the six perfections; and when this mind of bodhicitta is directed toward higher beings, it becomes a seven-branch offering. This bodhicitta nectar is what purifies the afflictive emotions in the minds of all sentient beings. On the bottom of page fifteen the text refers to it as ablution water endowed with samadhi and mantra, a vast ocean of good qualities. This is the quality of bodhicitta, and we have a vast ocean of bodhicitta here. With such vast bodhicitta you should visualize the deity and recite the mantra.

Next it says: Bathe your lotus mind in the moon mandala reflected in the water of primordial wisdom. With this, the water becomes the nature of primordial wisdom, which ultimately represents the nature of emptiness, symbolized here by the moon reflected in water. Sentient beings are confused, believing in the true existence of appearances and their conceptual labels. To them, things appear in a concrete way. The nectar here purifies the stains of this confusion in a two-fold manner, on both the relative and ultimate levels. On the relative level, self-clinging is purified through love, while the truth of emptiness and non-dual primordial wisdom purifies beings on the ultimate level. Externally we are performing a ritual purification, but on the inner level it is really a purification that happens through the power of the two-fold truth, the relative and the ultimate. The cleansing really happens from mind-to-mind.

Then on page seventeen, the text speaks of spacious bodhicitta. Here, because you love these beings, you want to give them everything. For example, if you have a companion whom you love very much, you want to give them everything—all your wealth and enjoyments, holding nothing back. This is the nature of bodhicitta. When there is great bodhicitta for all beings, there is no self-concern whatsoever. At that point one has attained the level of a bodhisattva, and a bodhisattva is happy at all times. The instructions starting on page seventeen really apply to anyone—those who have passed away as well as those who are still alive. Through these instructions we give rise to faith in the Three Jewels.

On page eighteen, the text talks about the relationship between the afflictive emotions and primordial wisdom. As mentioned, there are five afflictive emotions in the mind-streams of sentient beings. Primordially, the mind is like a clear crystal from which five-colored rainbow lights emerge: one’s nature of mind has these five qualities as the five wisdoms. When the mind becomes obscured by self-clinging, these qualities appear as faults. They become the afflictive emotions, each of which is related to an aspect of primordial wisdom. If you understand this connection between them, you will know that all five qualities are inherent within your own buddha-nature.

The text shows this connection through the example of anger, and that the denizens of hell arise out of anger; see them as a mirror—clear and empty. From an impure perspective, when anger arises, it is just anger. When you believe in the true existence of anger and label it with various ideas, this is clinging to anger. It is from this aggressive mind that the hell realms naturally appear. Actually, anger and hell are not separate. Whether we are alive or not, this is the very nature of anger. For example, some people in this world are very wealthy and enjoy many pleasures, as if living in the god realms. Even so, many of them commit suicide. If you understand this—for example, that hell is nothing else but a projection of anger—then you can’t help but trust in karma. Here we are not even talking about anything religious, as some people say they don’t need these instructions since they do not consider themselves religious. However, it actually has nothing to do with religion—this is only explaining how things really are. When you recognize this, you recognize that your only true enemy is your anger. Your own anger is the only thing really polluting your mind.

So what is the method for eliminating anger? When it arises, you should first recognize it with clear awareness. When we take the refuge vows, we are introduced to this awareness as being the Buddha within your own mind, the perfection of wisdom. It is the clear mind free from all thoughts. When you recognize clear awareness, this awareness will naturally see the fault of anger, the true enemy, the moment it arises. Then you train in sustaining this clear awareness. You no longer focus on the outer object of your anger, but instead you look at your mind with clear awareness. Then the anger will disappear, and the mind remains in a pristinely clear and empty state.

This clarity is much more powerful than the clarity you would develop if you were to meditate quietly and peacefully for a whole month. This pristine clarity is referred to as “mirror-like wisdom,” and is the essential nature of anger. Anger is such a powerful force that its arising causes all other thoughts to stop. It overpowers all other thoughts, and you become completely controlled by it. This is why clarity is associated with anger. Here, anger is like wood, and clear awareness is like fire. Where wood encounters fire, there is no more wood—the wood itself becomes the fire. This is how we deal with each afflictive emotion. This is the skillful means of the Vajrayana, where we do not abandon or reject the afflictive emotions, but instead practice with them and turn them into the path. This is explained here through relating the five afflictive emotions to the five kinds of primordial wisdom. Knowing that the five afflictions ripen into the five wisdoms appearing in the form of the five Buddha families, it is enough just to take anger as an example, as the same principle applies to all the other afflictions. In the Samantabhadra Prayer it says: “When you recognize this, you are a Buddha.” From this appear countless enlightened forms, pure lands, and so on.

On page nineteen in the second paragraph, we tell these beings: Realize the three planes of the gods’ abodes within the state of clear and empty wisdom. We talked about the six impure samsaric states, which by nature are the abodes of the six pure wisdoms. This is really the essence of all practice. For example, on the Path of Individual Liberation, the afflictive emotions are abandoned. Then on the Bodhisattva Path, the afflictions are transformed through love and compassion—for example, because a mother loves her child, her six afflictive emotions will naturally transform into the six perfections. Finally, on the Vajrayana path, you understand the nature of the afflictive emotions, and it is only through this view that you will be able to free yourself from grasping at the true existence of appearances. Knowing that appearances are empty, you will not label them. In this way the afflictions transform into primordial wisdom.

On page twenty, the text explains resting in the state of mahamudra to them: Within the single empty nature of the mind itself, even the concepts of pure or impure do not exist. Enter the heart of awareness—the mandala of spontaneous, empty clarity! When you see the nature of mind, you experience a state of clarity that is empty like space. An outer example of this nature is the image of Samantabhadra yab-yum. The male and female in union represent the unity of clarity and emptiness that is the natural state of mind. The clarity aspect is represented by the yab, the male, and the emptiness aspect by the yum, the female. If you really understand the nature of afflictive thoughts and emotions through the view, clear awareness will cause them to collapse naturally. All forms of afflictions are dealt with the same way: they dissolve through sustaining mindful awareness. Within the natural state, not even the concept of pure or impure exists. Buddhas and sentient beings, samsara and nirvana, pure and impure are in essence empty of self-nature.

The mandala of spontaneous empty clarity has the quality of the five wisdoms and the three kayas. The dharmakaya, for instance, is the empty essence of the mind which is also naturally clear—it is clear awareness that is self-knowing of its own empty essence. Clarity and emptiness are not separate. Their inseparable nature is all-pervasive, and this all-pervasiveness is compassionate responsiveness. When you realize this nature of mind, you experience great bliss, realizing that the mind is never born and never dies. Thus there is no suffering, no fear. Only those who do not realize the nature of mind cling to a dualistic existence, and due to this clinging, they wander in samsara. So the text says: Enter the heart of awareness, and this means that one should recognize the nature of mind and sustain awareness of it. It means to remain within a state of non-distraction single-pointedly, unmoved by thoughts and emotions.

At the bottom of page twenty and twenty-one are the words of homage, where we prostrate to the guru and the Three Jewels. On page twenty-two, the homage ends with I pay homage to the Sangha. Among the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha, which one is really most important to us? Actually, it is the Sangha. It is said that even though the guru’s qualities equal those of the Buddha, his personal kindness to us is even greater. And the guru is the Sangha.

A “Sangha” is someone who is free from self-clinging, free from samsara and suffering, and is therefore able to show others the method for becoming free. Thus, of the Three Jewels, the Sangha—also referred to as “the excellent field”—is truly the most precious jewel. Any virtue of body, speech, and mind that we direct toward the Sangha becomes even more virtuous. And within one Sangha member the Three Jewels of the three times are complete. In particular, from your own perspective, the Sangha is represented by the guru’s body, the Dharma by his speech, and the Buddha by his mind. This is especially true for the guru to whom you are closest, the one who gave you the refuge vows, empowerments, and instructions. That is your main guru, and you should see this guru as the embodiment of all the buddhas of the three times.

On page twenty-three we pay homage to the three kayas—the dharmakaya that is like space, the sambhogakaya that is like a rainbow or clouds in the sky, and the nirmanakaya that appears in the form of the beings of the six realms of samsara in order to benefit sentient beings. So here you should give rise to faith in the qualities of the buddhas’ three kayas.

On page twenty-four, we again supplicate and pay homage, here on behalf of those who have passed away, as well as those who are still alive, even if they are not actually here in person. As Sangha, we represent them all when we supplicate. So, first we supplicate, then we seek refuge, and then we supplicate again for all beings, so that they may be liberated from the evil states of samsara. Here prostration is offered before the vajra master. Think that all sentient beings who suffer in the three realms of samsara are prostrating and seeking refuge together in the presence of the field of accumulation—the buddhas abiding in the space before you—and that you prostrate on behalf of them.

As for the method of accomplishing this practice for others, the one performing this inscription ceremony should develop faith and devotion in the Three Jewels from the bottom of one’s heart, and think that their own mind is non-dually inseparable from the minds of all other beings. If you as a Sangha member have developed conventional bodhicitta—immeasurable love—then this mind reaches all those beings naturally due to the inseparability of samsara and nirvana and the non-duality of self and others. In particular, if you have seen the ultimate truth and have realized non-duality, then through your realization you can clear away the confused dualistic perceptions in the minds of those beings. You can benefit them directly. When your state of mind arises in their minds, instantly their impure illusory forms transform into pure illusory forms of the yidam deities. So in the last line on page twenty-four it says: In an instant you departed ones transform into the pure deity.

On page twenty-five, empowerment is conferred through the wisdom nectar. On the relative level, this wisdom nectar might appear in the form of mani or other blessing pills, or as other kinds of blessing substances. On the relative level it has the nature of bodhicitta. Its ultimate nature is the view, which is the nature of mind. Through receiving empowerment, the obscurations of body, speech, and mind are purified. When there is no grasping at form or the body, this is called “appearance-emptiness,” or form appearing like a rainbow. When there is no grasping at sound or speech, this is called the empty sound of mantra. And when there is no grasping at what arises in the mind, it is clear and empty awareness.

In a text explaining the benefits of empowerment, it says that by having received an empowerment, even if one does not actually engage in its practice during this life, by having devotion and faith the benefits of the empowerment will ripen within seven lifetimes. So the reason I am offering empowerment over the live-stream and recordings is that those who possess faith can actually receive an empowerment in that way. What is most important is faith and devotion, and when they are present, the meaning of the empowerment will eventually ripen in one’s mind-stream. In brief, if the mind is clear and empty, then there will naturally be no grasping at form or sound, which is the very essence of the three empowerments.

On page twenty-six and twenty-seven we perform the burnt offering for the deceased. The meaning of the words we read here is love, in essence. As was explained, we are able to help those who have died through a bond of love connecting us to them. Though we have no other choice but to leave this body behind, what always remains is this bond of love within the heart. This will never cease to be. We must seal this love with bodhicitta, and then seek refuge in the Three Jewels. In this way we will be protected in future lifetimes. Here think that you are dedicating this offering to these beings, and that you accumulate merit for them. As a result, think that these beings experience great joy and happiness. The words here are very clear, and it is also very meaningful to chant them in verse form.

In the last line of page twenty-eight, we request: May it all turn into an inexhaustible supply of food and drink. May they all be satisfied. If these beings are able to give rise to bodhicitta, the pure lands will manifest to them naturally, and they will become free of all misery and suffering. In pure lands such as Dewachen they will enjoy their own self-projections, so we wish that beings be benefitted in this way for as long as samsara exists. The prepared sense pleasures of form, smell, and so forth are now consecrated and dedicated. We request that through this, May the clinging to the six sensations be freed in its natural place. This means that when bodhicitta is present, there is no attachment to the six sense objects. Even though one may still enjoy any of the sense objects, by virtue of the power of the ultimate truth there is no attachment to them.

The words on page thirty-four are clear and do not require much explanation. Their essence is that one should not be attached to samsaric existence. Then at the end of the page we bring to mind the Buddha Amitabha in an instant. Directly think of Amitabha single-pointedly, without thinking of anything else. This is all that is required: simply bring Amitabha to mind. To do this, the one who is performing this ritual first needs to have faith in the Buddha Amitabha and the pure land of Dewachen. Then with a faithful mind, bring to mind Buddha Amitabha and Dewachen, and think of those beings who have passed away. Through your connection to them, this state of mind will also arise in their minds. If you do not develop faith—if you just recite this text without any faith while visualizing Buddha Amitabha—there will be no benefit, so the practice must arise from your own faith. This is significant because self and others are indivisible. Thus, it is crucial here to develop a feeling of faith, which is then is transferred to the other person. This is how the transference of consciousness, or phowa, is performed.

On page thirty-five, the sadhana says that the consciousness in the form of AH dissolves into the heart of Amitabha. From the ultimate perspective, there is no duality. There is no one who transfers and no place to transfer someone. Only when helping those who still perceive a dualistic existence do we say that there is a place to go, and that you have to go there from here. Actually, Lord Jigten Sumgön said that the Dharmakaya Phowa of Luminosity Transference of the Consciousness into the Luminous Heart of the Guru is the ideal method. This is the true essence of phowa, the supreme method. If you are very devoted to your guru, all that is necessary is to bring the guru to mind. Then there is no other phowa visualization or practice required— you just bring the guru to mind. The essence, the true nature of the guru, is the luminous mind— your ultimate true nature. On that level, there is no duality of transferring the consciousness and somewhere to transfer it. That is the dharmakaya phowa. On the relative level, we tell beings who cannot comprehend this that there is a pure land called Dewachen, and that it is where you want to go, so set your aspiration and cultivate faith in the Buddha Amitabha. And if you do so, even on the relative level, liberation is certain. Liberation really means liberation from self-clinging through bodhicitta. The pure land of Dewachen is only the projection of the natural radiance of bodhicitta.

There is an extremely important point here in the last line of page thirty-six, and that is if you do not attain enlightenment in the first bardo, there is an opportunity to attain enlightenment in the second bardo. To train yourself in this, when you fall asleep, every time you wake up you should instantly remember the yidam deity. For example, the moment you wake up you think of Buddha Amitabha and recite a few OM AMI DEWA HRI mantras. Or it could be Avalokiteshvara or any other yidam deity. If you are able to bring to mind the yidam deity upon awakening instantly, the yidam deity will also appear to you immediately upon awakening in the second bardo.

This happens because your true nature is buddha-nature, which is forever undefiled by any stains. From within that state, the Buddha Amitabha appears naturally through your own faith and trust. The mind becomes the deity the moment you think of it, and all temporary confusions of self-clinging will not arise. When you really trust in the deity, the practice of the deity is very powerful. First you must have a good motivation, and then you bring the deity to mind in an instant. For example, Avalokiteshvara appears in your mind instantly. It is not so important whether or not the deity appears clearly; what is most important is to fully trust that what appears is actually the deity. So if you fully trust in Amitabha, for example, and you bring to mind Amitabha in an instant, then in that moment your mind has transformed into Amitabha. And because Amitabha and the pure land of Dewachen are indivisible, the pure land of Dewachen will also manifest naturally. This is an important instruction, and if you understand it clearly, it is undeceiving. It is an ultimate instruction, and the actual meaning of phowa.

On page thirty-seven it says: By the force of the noble and supreme conquerors’ compassionate blessings and our faith, our mind-streams blend non-dually in a mere instant. The buddhas of the three times love sentient beings as a mother loves her only child, and are only concerned with the well-being of sentient beings. If you are free from doubt and give rise to faith in Buddha Amitabha, then in an instant you will merge non-dually with Buddha Amitabha. It is just like when you think of a friend whom you love very much—it is like you are merging into one with them. Like that, if you bring to mind Amitabha with firm trust, in an instant you can merge non-dually. On the ultimate level we are already non-dual, so it is like a block of ice melting into water. If you have that trust, then with one hundred percent certainty you can be sure that you can become Amitabha. This is actually the most important part, and it is quite easy to understand. In brief, if you have faith and trust, even if you are not able to practice in this life, you can still merge with the Buddha Amitabha. For example, if I ask you, “Do you trust in the Buddha Amitabha?” and you answer yes, then all you need to do is always bring to mind the Buddha Amitabha, especially when you encounter difficulties. This is actually sufficient. By virtue of your buddha-nature, the moment you think of Amitabha, you have already become Amitabha.

On the last line on page thirty-eight it describes that the fire of wisdom awareness is lit upon the woodpile of self-clinging. This is the most important line here. Self-clinging and all dualistic grasping are burned away by love and compassion. Non-dual primordial wisdom burns away all grasping at a concrete reality and all conceptual labels. This is very similar to the instructions on the nature of the mind that we often receive.

At the end of page forty-three, there is an image representing everything included in this offering of the “Inscription for the Dead.” The various materials needed are listed in the extensive sadhana elsewhere. The various objects of enlightened body, speech, and mind are all complete within this image. This particular image comes from a previous Garchen Rinpoche, and within it all the offering substances—the five sense pleasures and all the other materials—are complete. It is very beautiful, which is also meaningful, as the offering substances should be pleasing. Since everything is included in this image, it is not necessary to create a separate image with a separate syllable for each person. One of these images of the syllable is sufficient for all the consciousnesses together. We can just think of it as a nice hotel to which we invite hundreds and thousands of different consciousnesses. This image is very important for the practice.

Regarding permission to perform this ritual for others, as I mentioned before, you must have taken the refuge vows. This is very important. People have different opinions about who should be permitted to perform this ritual, but my opinion regarding this is quoted in the Samadhi-Raja Sutra in the section which explains the benefits of taking a vow. It explains the difference in merit between having taken a vow versus not having taken a vow. If you have received any vow, such as the refuge vows, this makes all your virtuous practices much more powerful.

There was a great Gelugpa Geshe called Ngawang Phüntsok, a great Lamrim master with many disciples in the Gelugpa lineage. Many people know him; he is a very precious lama, and in 1979, I received the Mahayana Sojong Vows from him. In terms of taking versus not taking vows, he taught that when you make offerings after having taken a vow—for example, if you offer a drop of butter, a butter lamp, or any other offering even as small as a needle’s point—this offering becomes more powerful than offering an entire ocean of butter or a mountain of offerings when you have not taken a vow.

These instructions are very meaningful when applied here. We mentioned before that when you take the refuge vows, you become a citizen of the country of the Three Jewels. And if you take the bodhisattva vows, you develop confidence and trust in the quality of love. Actually, no one can tell you that you are allowed or not allowed to do these rituals. It is something that you can only see for yourself by looking at your own mind. And if you find that you really do hold these vows and you really do have love for all sentient beings, you have the permission to perform this ritual. These are the actual criteria.