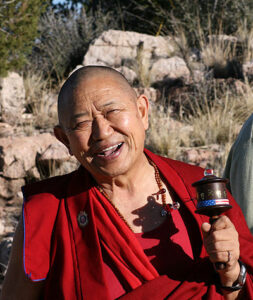

Six Mantras and Six Mudrās by H.E. Garchen Rinpoche

Translated by Ina Bieler

The Six Mantras and Six Mudrās are performed during a smoke offering (sang) or a burnt offering (sur for bardo beings.) The “six mantras and six mudrās” refer to six deities belonging to the five buddha families. It is said that the six mantras and six mudrās possess great blessings. They clarify the nature of all the offering materials. They show how these offerings first come about, and then how they are received by gods and humans. The six mantras and six mudrās are very important whether we perform a sang or a sur.

The mudrās are performed while reciting the mantras. Of body, speech, and mind, we perform the mudrās with the body—the lotus circle and so on. As for the mudrās, they are performed with one’s hands, which have ten fingers. As for the symbolism of the ten fingers: in one’s mind are the five afflictive emotions. If the mind connects to bodhicitta, they become the five buddha families. The outer body consists of the five elements. If one connects to bodhicitta, they are purified and transform into the five Mothers. In brief, the body has the nature of the five buddha families yab-yum. Thus, the body is also connected to the outer five elements. The outer natural environment—the trees and plants, the forests, herbs, and grains—all are connected to the sky and the earth; everything arises from the four elements.

In the inner mind, the mental continuum—in the mind of all the buddhas are the five wisdoms. When the five afflictive emotions ripen, they become the five wisdoms, the five buddha families. The Samantabhadra Prayer says, “From these five wisdoms, the five original buddha families emerge.” The body has the nature of the five buddha families yab-yum. The universe and beings, the natural environment, is all nirmāṇakāya. Thus, it is taught that the five buddha families yab-yum are nirmāṇakāya by nature. Everything lacks inherent existence; it arises through dependent connection. This means that saṃsāra is naturally created dependently upon self-grasping, temporarily, like an illusion, like an ice-block in water. In dependence upon bodhicitta, the pure lands and buddha forms are naturally created. Now we perceive things in pure and impure ways. Impure perceptions are confused perceptions, because in its natural state, everything is pure.

Through the mudrās we transform impurity into purity—but really, we do not have to actually transform anything, we just understand the true nature of things. The mind gives rise to bodhicitta, the body performs the mudrās, and the speech recites mantra, the words of the Buddha. If you join [the mudrās] with the Sanskrit syllables of the mantra, you unite body, speech, and mind into one. All of this arises by virtue of three powers. First, there is the power of your own intent; you need bodhicitta. Then there is the power of the tathāgatas: all the buddhas possess the powers of mantra and bodhicitta. Finally, there is the power of dharmadhātu: nothing possesses any inherent existence; all phenomena of saṃsāra and nirvāṇa are adventitious, like illusions; they arise through dependent connection. Saṃsāra arises due to self-grasping. The altruistic mind creates the pure buddhas, the pure lands, and so forth. In sum, everything is complete within the sphere of the buddhas’ three kāyas. Thus, the six realms of saṃsāra belong to the sphere of the nirmāṇakāya, where pure and impure co-exist.

Through the wisdom and compassion in your own mind, you can understand that what appears impure is actually pure. This blesses all those who do not understand.1 Once the adventitious confusions—the dualistic thoughts of pure and impure—are dispelled, what remains is natural purity. Seeing things as impure is an adventitious confusion; things are pure by their very nature. For example, the peel of a fruit might be impure, but once you take it off, you can eat the fruit inside.

The purpose of the Six Mantras and Six Mudrās is to dispel the stains of impure, confused perceptions. First it says, “OṀ SVABHĀVA ŚUDDHĀ SARVA DHARMA SVABHĀVA ŚUDDHŌ HAṂ. ” Nothing exists inherently; everything is emptiness. However, even though nothing really exists, we can see everything. We can see buddhas and sentient beings, the universe and beings. What are we seeing? Everything arises through dependent connection. From bodhicitta, the pure lands arise; and from self-grasping, the six realms of saṃsāra—and they, too, are just an adventitious stain. So we transform everything impure into pure. Then it says, “NAMAḤ SARVA TATHĀGATE BHYO VISHVA MUKHE BHYAḤ.” The yab and yum of the five buddha families unite. Through their union, the entire universe and all beings are blessed; all the offering substances become so vast they fill the entire sky. “NAMAḤ SARVA TATHĀGATE:” the five male buddhas unite with their consorts. “BHYO VISHVA MUKHE BHYAḤ / SARVA THĀ KHAṂ UDGATE SPHARAṆA IMAṂ GAGANA KHAṂ SVĀHĀ.” Snap the fingers once. Think that the offering materials are created instantly, naturally, from within the state of emptiness. Nāgārjuna said, “Since everything is empty, everything is possible.” The offering materials pervade the sky; they fill the entire space of the universe. They are actually established naturally.

Like rainbows in the sky, like the clouds and rain, and so forth, they all arise naturally. For example, when you cook food, the best part, the vital essence, actually goes up into space [as the steam.] What we eat is really the dregs of the food. The primary vital essence goes outside, but it also returns in a different form. Here you should recognize that the [offerings] naturally pervade all of space. They pervade the nature of the pure deities. Even though they also pervade impure sentient beings who grasp at duality, because those beings perceive a difference between self and other, unless the offerings are dedicated to them, they cannot eat them. For example, if you visit a rich family’s home, even though their house is full of food, if they do not offer it to you, you cannot eat it. Due to their dualistic grasping, these beings have fear. Because of dualistic grasping, they perceive self and other, and due to this concept of a self, fear arises. Only if you bless the offerings and dedicate them to all the impure sentient beings of the six realms can they receive them. The buddhas know that these offerings are present naturally. “BHYO VISHVA MUKHE BHYAḤ” (means Blessed by the mudrās, mantras, and bodhicitta) buddhas pervade the entire space. Then, “OṀ VAJRA AMRITA KUNḌALI HANA HANA HŪṀ PHAṬ.” It is bodhicitta, the unity of emptiness and compassion—for example, Samantabhadra with consort.

The outer form of yab and yum represents the inner unity of emptiness and compassion. Through this blessing, all offering materials become food of love, a vast ocean of nectar. “OṀ VAJRA AMRITA KUNḌALI HANA HANA HŪṀ PHAṬ.” Even if you only have a small amount of food, if it is given with love, it is delicious. When it is sealed with love, it becomes like mother’s milk. Thus, it says “All the materials become a vast ocean of nectar.” What is the meaning of “nectar” (dü-tsi)? For sentient beings without realization, the afflictive emotions are like a demon (dü), because they bring suffering. If you exchange self-grasping for altruism, then the six afflictive emotions will become the path of the six perfections—generosity, morality, patience, and so forth—with love and compassion as their cause. Regarding the “dü” (demons) of afflictive emotions: when everything impure is made pure, they will receive our offering. By seeing, touching, or tasting this offering, bodhicitta will arise in their minds and self-grasping will be purified. Bodhicitta arises in their mind-streams, thus, “OṀ VAJRA AMRITA KUNḌALI HANA HANA HŪṀ PHAṬ. All the materials become a vast ocean of nectar.” Then, “NAMAḤ SARVA TATHĀGATA AVALOKITE / OṀ SAṂBHARA SAṂBHARA HŪṀ.”

The five objects that please the five senses, plus the sixth mental consciousness, are offered to those who grasp at a duality of self and other, and come to accord with their wishes. For example, some want salt, others want chili pepper; beings with dualistic perceptions have various needs. So, “All the materials come to accord with the wishes of the guests.” They become whatever is desired: the three white and the three sweet substances, various enjoyments, tea, or beer. Think that through the blessings, the substances accord with the wishes of the guests. Then, even though they accord with their wishes, if they are not given to those with dualistic minds, they cannot be received. “OṀ JÑĀNA AVALOKITE / NAMAḤ SAMANTA SPHARAṆA RASMI SAMBHAVA SAMAYA / MAHĀ MAṆI DURU DURU HRIDAYA JVALANI HŪṀ.” Now you should think that you are like Chenrezig, and you have love for all. Therefore, you possess perfect power. For example, you can say “Come and eat at all the restaurants all over Taiwan. You can eat as much as you want, and you don’t have to pay.” Like recently when someone offered us food and we could eat as much as we wanted. Thus, “The guests receive all the materials without any loss, gain, or conflict.” It is inexhaustible, you can eat as much as you want. Then it says, “NAMAḤ SAMANTA BUDDHANĀṂ GRAHEŚVARI PRABHAJÑATI MAHĀ SAMAYA SVAHĀ.” Then all self-grasping, pride, and arrogance are pacified. Everyone is grateful for receiving the delicious food that comes from bodhicitta, and they all rejoice and pay respect.

So it says, “All the guests are brought under my power,” and you perform the victorious mudrā circle of overpowering with “NAMAḤ SAMANTA BUDDHANĀṂ GRAHEŚVARI PRABHAJÑATI MAHĀ SAMAYA SVAHĀ. All the guests are brought under my power.” What kind of power it this? It says, “Namo! By the force of my intentions…” It is a genuine altruistic intent, the same as the intent of the buddhas. You have to think: “I truly want to benefit sentient beings; I have no other wish than that.” Second, it is the power of the tathāgatas. All the buddhas of the three times possess inconceivable, naturally existing, meritorious enjoyments, equal to the limits of space. This is the power of the tathāgatas. Those beings with adventitious, confused perceptions, who experience heat and cold, hunger and thirst, can enjoy these offerings. Third, it is the power of the dharmadhātu. These are only temporary, confused perceptions. At the basis, there is no duality. They are all buddhas. Their nature is primordially pure and spontaneously accomplished. Thus, the offering materials appear naturally. They emanate from oneself and are enjoyed by oneself. There is no duality between the one who offers and the one who receives the offering. This is “saṃbhoga” or “complete enjoyment.” One is enjoying one’s own projections. There is no self and other. There is no duality between the host and the guest. For example, a big tree has many branches and blossoms. It seems that interconnected branches are separate things, but the basis is the same. There is nothing but one’s own projections. It is like you are enjoying your own self-projections. When there is no grasping at a self-other duality, you can enjoy things offered by inconceivable offering goddesses. In brief, you enjoy them without being controlled by them.

Because by nature self and others do not exist, there is the power of the dharmadhātu. Dualistic existence is only a temporary state of confusion. Knowing this to be confusion, non-duality will slowly become apparent. In the end, all dualistic grasping is cleared away and non-dual primordial wisdom will expand. It is beyond the limitation of being either one or many. “One-taste as multiplicity” means that there is no duality in buddha-nature. Buddhas and sentient beings are not two. Nonduality is “one taste as multiplicity.” Just as there is only “one” water, even if it is divided into many. There is only “one” water but there is also a vast ocean. This is “multiplicity as one taste.” There is only “one” water. “One taste as multiplicity” means that there is the ocean, clouds, rain, water everywhere, you can use it to wash yourself, you pee it out, but it all functions as water. You should understand well “multiplicity as one taste” and “one taste as multiplicity.” Understanding this is the power of the dharmadhātu. At the basis, there is no duality. So, there is the power of your own intent: this is bodhicitta. Second, the power of the tathāgatas: on the relative level, all the buddhas possess immeasurable love and compassion. And third is the power of the dharmadhātu: on the ultimate level, there is no duality. There are no separate buddhas and sentient beings. Then it says, “…in order to make offerings to the noble ones…” The offerings to the noble ones are naturally there. Then it says, “…and to benefit sentient beings, all aims and wishes we might have—all of them, whatever they may be, in all of the worlds without exception—may they arise without hindrance.” Nothing is owned, you can receive everything. The Six Mantras and Six Mudrās is extremely important, its meaning is excellent and should be understood. In brief, they are the names of the six tathāgatas. This is the meaning of the Six Mantras and Six Mudrās.

Translated by Ina Trinley Wangmo and edited by Kay Candler in 2018.